Our course participants expect clear instructions from our instructors that they can remember and recall in stressful operations and put into practice. For example: «The reconnaissance team does not rescue!» But how can exceptions to such rules be communicated without losing their conciseness? Our full-time instructors addressed this question during their internal advanced training. In doing so, they came across a helpful concept in linguistic logic: universal quantifiers. These are words such as «never, always, all, everyone.» They also discussed the use of modal verbs such as «must» and «should» in teaching statements.

Small words with great significance

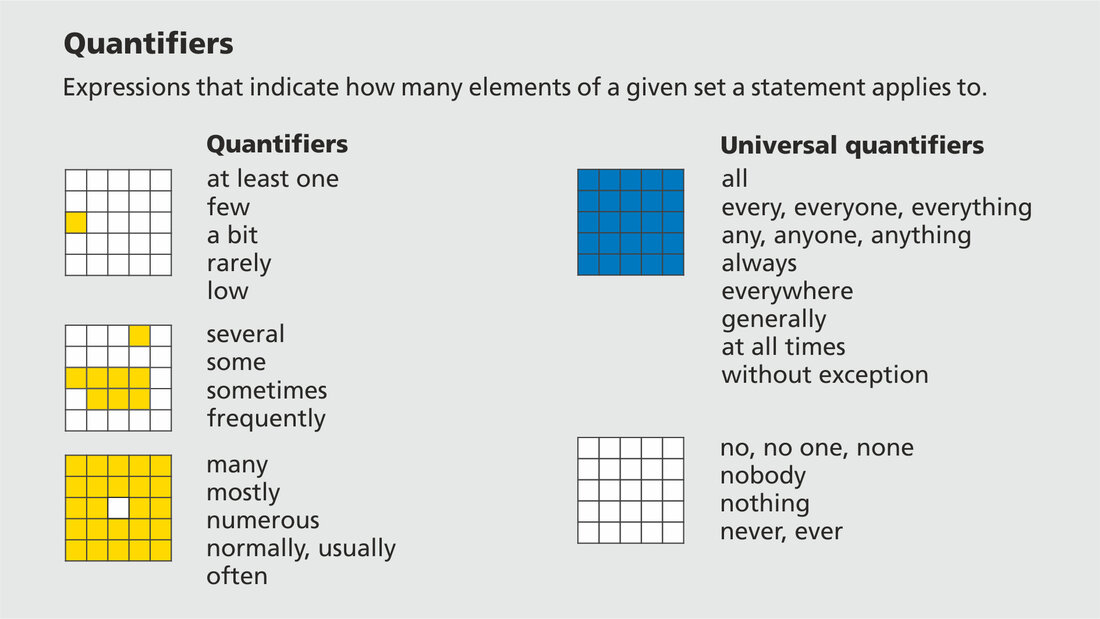

In linguistic logic, quantifiers are expressions that specify how many elements of a given set a statement applies to: For example: «Many tunnels have emergency exits.» Universal quantifiers, on the other hand, make a statement about all elements of a particular set. For example: «All tunnels have portals.»

Are there really no exceptions?

Universal quantifiers create clarity by reducing complexity. A statement such as «The reconnaissance team never rescues anyone!» would allow for no exceptions. «Never» means «never.» However, there are situations in which the reconnaissance team is also supposed to rescue people. The International Fire Academy instructs: If the team encounters a helpless person within the first ten meters of its reconnaissance route, the team rescues this person. However, if the team has already penetrated further into the tunnel, it marks the location and calls for a search and rescue team. The correct teaching statement is, therefore, for example: «As a general rule, the reconnaissance team does not carry out rescues.»

Rules alone do not suffice for training

The didactical problem is: In order to apply rules correctly, one should also understand their background, meaning and purpose. These must be explained: The reconnaissance team should not rescue «never», but only not over long distances. Firstly, delayed reconnaissance could jeopardise the success of the operation. Secondly, the reconnaissance team is not equipped for rescue operations. He also does not carry fire escape hoods or carrying aids with him. Only the requested search and rescue team can protect the person to be rescued from fire gases with a fire escape hood and quickly carry them out of the tunnel using a basket stretcher with wheels.

Experience gives meaning to rules

But even the theoretical derivation of a rule is often not enough to be able to apply it effectively during deployment. Course participants frequently ask why the reconnaissance team should not also be able to rescue people from a distance of 50 or 100 meters. The answer comes from practical experience. After a few training drills, our course participants know how difficult it is to carry an unconscious person over long distances. And how quickly, on the other hand, a search and rescue team can do this with a basket stretcher with wheels. This experience helps in weighing up the situation to determine which approach will lead to the goal more quickly.

There are almost always exceptions

A detailed explanation of all teaching statements would be desirable, but this is hardly feasible in the available training time and can lead to learners being overloaded with information. That is why concise teaching statements are indispensable. However, to ensure that these are not followed «blindly,» possible exceptions should be indicated by using phrases such as «as a rule,» «in most cases,» or «normally.» It encourages course participants to weigh up for themselves how the rule should be applied in different situations during practice and deployment.

Say «always» when you mean «always»

On the other hand, universal quantifiers should be used deliberately as a linguistic device where absolute statements can give learners certainty: «A representative of the infrastructure manager must always be involved in operations on railway facilities.» This statement means: It is never wrong to first contact the responsible railway company before emergency personnel take action on the tracks. It is because firefighters cannot directly influence railway operations. They cannot discontinue railway operations or stop trains.

Is an action really necessary?

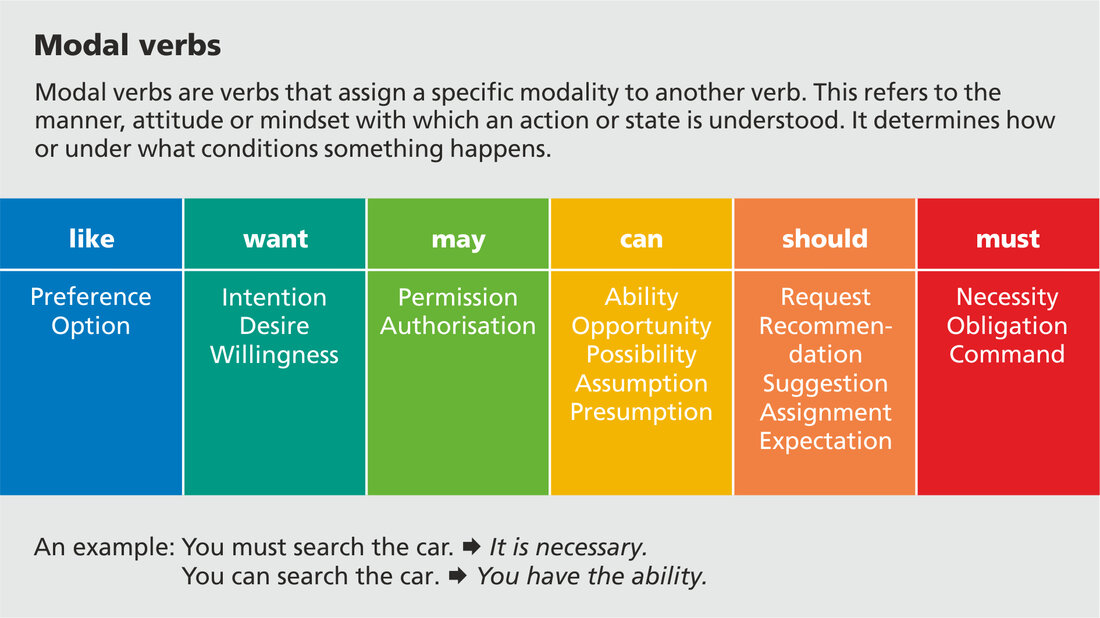

The situation with modal verbs is similar to that with universal quantifiers. They are listed in the following table. When is the statement that something must be done – or must not be done – really correct? Again, our instructors' self-reflection showed that absolute statements are rarely justified.

When «must» and when «should»?

One example of a teaching statement in which we deliberately use the word «must» is: «When working on railway installations, the overhead lines on both sides of the work site must be switched off and earthed.» The consequence: It is right to wait until the grounding has taken place. «Should,» on the other hand, means to do something as far as it is possible and appropriate in the situation. Due to the generally better working conditions on the upstream side of a fire, the fire attack should be carried out there. However, there are situations in which this is not possible or in which firefighting on the downstream side leads to the desired extinguishing success much more quickly.

Know and communicate exceptions

«The distance between two emergency exits in a road tunnel on Swiss national roads must not exceed 300 meters.» That is what the regulation states. That's how it usually is. But that's not always the case: The following image shows an emergency exit door damaged in an accident, which temporarily doubled the distance between emergency exits here to 600 meters.

Operational situations are extraordinary situations

Of course, it does not make sense to base our operational procedures on such rare exceptions. However, we believe that comprehensive training also involves preparing our course participants for the fact that many operational situations do not conform to standards or common sense. That is why we try to identify and communicate possible exceptions and clearly state the few things that «always» or «never» apply and what «must be» or «must not be.»

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/f/csm_ifa_MAG_088_Action_010_06f29aa26b.webp)